by Blaze Ardman

Cemeteries don’t rank high on my list of places to go on my summer vacation. That’s not to say I’ve never meandered through one or two really old ones. Pulling back the weeds to check out ancient headstones, the engraved names barely discernible, worn away by time. But this cemetery in which I now find myself is different. It’s new and modern and it contains my personal history. The marble glistens, and even though my father just passed away six short weeks ago, his name is already carved next to my mother’s on their “True Companion” vault, six levels up, with a water view.

This is my fifth visit to this cemetery, and the first one I’ve made by myself. After my mother died, on my subsequent trips to Florida to see my dad, he and I went together. I wouldn’t have minded a solo trip, but he always insisted on accompanying me. Yet he also wanted to make a quick getaway, so we’d drive about an hour each way to hang out for just five minutes. Today, there’s no rush, and don’t I wish there were?

What wouldn’t I give to have him pacing — saying, “take your time, take your time,” and meaning, “hurry up, hurry up.”

The day is still young, and the temperature and humidity still low enough so I can be outside without curdling. A breeze blows in from the canal and a few herons strut on the shore. I park myself on a marble bench that bears the name of a stranger, Isaac Shoenfield. I pull my legs into as much of a lotus as they’ll go, silently thank Mr. Shoenfield and his family for the comfort this bench provides, and begin my first-ever cemetery meditation.

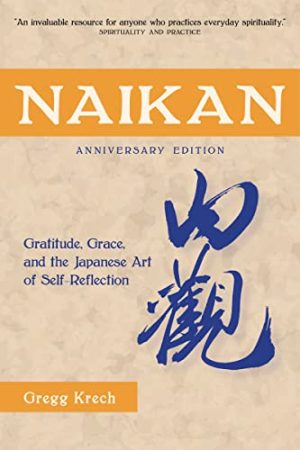

While driving to the cemetery, I wondered whether this visit was such a good idea. Going there would most likely restimulate feelings of loss and sadness. One of life’s great truths is that feelings fade with time unless restimulated. So why tempt fate? After all, I was really doing quite well. I could certainly meditate, do some Naikan reflection, and have a talk with my deceased parents in some other location. I could…but possibly wouldn’t. I knew this cemetery visit was necessary.

If unwelcome feelings appeared, I would just have to co-exist with them.

Better some moments of pain, loss and sadness now than future moments of regret for not taking this opportunity, which may not come again.

Suddenly I notice that I’m lost in a reverie of what was and wasn’t, what might have been, and what might or might not be, all things over which I have no control. A good way to increase my suffering. I shift my attention to the sensation of the marble, cool and smooth against my skin. I notice the sounds of the birds and wind, and the blue of the sky. It is a beautiful day and I have done what I came here to do. It only hurts when it hurts.

The pilot who flew me to Florida landed the plane without incident. The car I rented took me to my destination and upon my departure from the cemetery, its air conditioning keeps me comfortable as the noon sun blazes. A map guides me to the home of the friends with whom I will stay. When I get there, I can use their phone, electricity, bathroom, and swimming pool.

I have learned to take in more of reality than the fact that I have lost two parents in a short span of time, and that I did not do for them all that I wish I had done, and that I miss them like crazy. The “tools” provided by Japanese Psychology (Morita and Naikan therapies) have never served me better than when my parents died. Here are some of the ways in which one can put these tools to work in the midst of life’s losses.

- Remember that life is lived moment by moment. Instead of labeling your mental state as “depressed,” or “sad,” for example, acknowledge the reality that you are having a few, or even many, depressed or sad moments. There are also moments when you’re not depressed. When we stick labels on ourselves, we not only limit ourselves, we also make inaccurate generalizations. Feel blue in your blue moments, fearful in your fearful ones, content in your content ones, but don’t call yourself a sad or scared or even a happy person.

- Engage in constructive, purposeful activity, even while feelings of grief or sadness are strong. Physical exertion is especially useful. Tasks like vacuuming and washing the car put our attention on things outside ourselves, and increase our sense of accomplishment. Exercise! Brisk walking, jogging, bike riding, swimming, dancing, aerobics, and tennis increase well-being and physical fitness. They force you to pay attention to your surroundings, and to your body, thus reducing the intensity, frequency and duration of distraught moments.

- If you find yourself crying, just let the tears come while you continue doing whatever you’re doing. Crying relieves tension. Trying to fight tears is like trying to fight feelings. Not only is it useless, but tears, like feelings, often fight back if you try to hold them down. I find that if I don’t attempt to do anything about tears, they pass, just as feelings do. A few deep breaths can help restore equilibrium.

- Recognize that whatever you’re feeling is natural. There are no rights or wrongs or shoulds or shouldn’ts when it comes to feelings. There’s also no time limit after which certain feelings aren’t “supposed” to arise. When you miss someone, you miss someone, and there may be moments of missing a person even years after they’ve died.

- Open sympathy cards as you receive them. Don’t procrastinate until you’re “in the mood.” Knowing that others are thinking of you guards against an overindulgent self-pity. And acknowledge the cards within 24 hours if possible. When my mother passed away, I delayed my acknowledgments, while marveling at my father’s promptness. Later, it was a chore to acknowledge them all at once and I found myself wishing I hadn’t procrastinated so long. When my father died, I responded more quickly, often immediately after opening the cards. To my surprise, I found that thanking others for their expressions of concern was more than just good manners, it was also good therapy, reducing self-focus and placing my attention on what I had received instead of what I had lost.

- Do Naikan reflection every day. You can reflect upon the person who has passed away, as that is often what needs doing. You might also reflect on the person’s parents and others who played a role in the relationship. If the person was ill, you can reflect on the caregivers. (I caused the caregivers of both my parents quite a bit of inconvenience and trouble. They, in turn, made my life much easier.)

For me, daily self-reflection is very important. It shows me that there’s more to my life than my loss. I can’t recall a day when I haven’t received more than I’ve returned. Naikan also helps me keep tabs on how I’m doing with that part of my life that is in my control, my behavior. How did my actions or non-actions cause trouble or inconvenience to others today? Of what use or help have I been to others today? What did I not do that I could have done had I paid better attention or acted less selfishly?

-

Make an extra effort to be of service to others. Keep in mind that you are not the only person in your world who has problems or difficulties or needs. Others are suffering in many ways. Do something to help. Small, thoughtful actions or gifts are as good for you as for the other person. Looking for ways to be helpful forces you to be aware of things outside yourself, which naturally results in a clearer, larger view of reality. In the weeks right after my father’s death, I had occasion to be a designated driver, give away a small box of chocolates, lend someone a card table, and send a sympathy note to a friend whose cat died.

When someone we love dies, feelings of pain, loss, sadness, depression, bewilderment, anger, guilt, disbelief, numbness, confusion, worry, loneliness, fear, resentment, remorse, and even relief — to name a few — stampede right through us. The feelings come on so fast and so furiously that we seem to experience them simultaneously. One moment we’re in tears, and the next we may be quite composed as we do what needs doing. Then despair washes over us once more, and we’re convinced we’ll be miserable forever. How do we respond to this flood of emotions?

Perhaps by just allowing them to pass through us, accepting them, and returning to our life in the present moment, whatever that may be.

Death serves as a reminder that our time here, no matter how long, is limited and too precious to waste. Recently, I have begun to ask myself what I would regret not having done if I were to die tomorrow. Those answers, some of them quite surprising, help bring purpose more fully into view and help me to plan for the future.

These tools can help reduce unnecessary suffering, the “suffering upon suffering” that we unwittingly put ourselves through when, in the agony of loss, we lose sight of the bigger picture and sink into the quicksand of self focus.

In the end, nothing fills the emptiness when empty is how I’m feeling. Nothing makes me miss them less. Sometimes I wish they were still around. Twilight time is still difficult for me — a time when I often feel lonely and used to call my parents. Sometimes I still find my hand reaching for the phone as the setting sun gradually paints a glorious crimson sky. While feeling sad, I admire nature’s magnificent colors reflected in the water, bouncing off the Golden Gate bridge. It is reassuring to know that the sun will continue doing what it does, making each day, like each moment, a fresh one.

Blaze Ardman is a businesswoman and faculty member of the ToDo Institute. She has been a writer, editor, and founder of an alternative greeting card company. She recently completed a year as a volunteer with Positive Futures Network, publishers of YES! Magazine.

Cemetery Photo by John Robertson (creative commons: Flickr)

Airplane Photo by Papas Dos (creative commons: Flickr)

Blanket Making Photo by Shimer College (creative commons: Flickr)

Tags: depression gratitude Mental Wellness

Make an extra effort to be of service to others.

Make an extra effort to be of service to others.