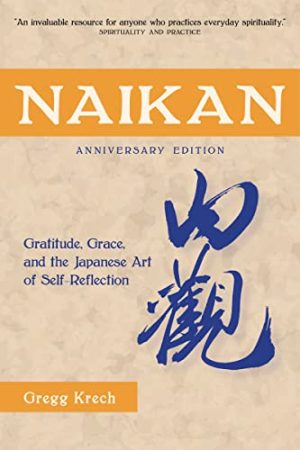

When I did my Certification Training in Japanese Psychology, one of the expectations was to simply apologize for mistakes. In other words, if you were late arriving to the class, or behind with an assignment, you apologized. No explanation or rationalization was permitted. This was hard for me to learn. To simply apologize or admit that I dropped the ball, without attempting to justify my tardiness or mistake, was unnatural, to say the least.

This lesson has stuck with me all these 30 years later, and I still struggle not to explain why I didn’t get done what I had committed to do, or that my claim was wrong. If I make an unkind remark, I immediately want to take it back and quickly explain to you that really, I am not impudent, but I am not myself today… my instinct is to try and convince you that it was not really my fault and there are reasons for my unkindness.

Justification is not the same as a simple explanation. e.g., I can’t make the meeting because I have been in an accident, as opposed to sorry I am late for our meeting, but traffic was heavier than I anticipated.

A great nation is like a great man:

When he makes a mistake, he realizes it.

Having realized it, he admits it.

Having admitted it, he corrects it.

He considers those who point out his faults as his most benevolent teachers. – Lao Tzu

Carol Tavris wrote a book 14 years ago and called it

Mistakes Were Made (But Not by Me): Why We Justify Foolish Beliefs, Bad Decisions, and Hurtful Acts

Here is a short excerpt:

“How difficult it is to say, “Boy, did I mess up,” without the protective postscript of self-justification—to say, “I dropped a routine fly ball with the bases loaded” rather than “I dropped the ball because the sun was in my eyes” or “because a bird flew by” or “because it was windy” or “because a fan called me a jerk.”

A friend returning from a day in traffic school told us that as participants went around the room, reporting the violations that had brought them there, a miraculous coincidence had occurred: Not one of them had broken the law! They all had justifications for speeding, ignoring a stop sign, running a red light, or making an illegal U-turn.

He became so dismayed (and amused) by the litany of flimsy excuses that, when his turn came, he was embarrassed to give in to the same impulse.

He said, “I didn’t stop at a stop sign. I was entirely wrong, and I got caught.”

There was a moment’s silence, and then the room erupted in cheers for his candor. There are plenty of good reasons for admitting mistakes, starting with the simple fact that you will probably be found out anyway—by your family, your company, your colleagues, your enemies, your biographer. But there are more positive reasons for owning up. Other people will like you more. Someone else may be able to pick up your fumble and run with it; your error might inspire someone else’s solution. Children will realize that everyone screws up on occasion and that even adults have to say I’m sorry.’

And if you can admit a mistake when it is the size of an acorn, it will be easier to repair than if you wait until it becomes the size of a tree, with deep, wide-ranging roots…it is a lesson for all ages: the importance of seeing mistakes not as personal failings to be denied or justified but as inevitable aspects of life that help us improve our work, make better decisions, grow, and grow up.”

How do you think this applies to you? As for me, it is a lifelong, challenging, and insightful practice.

Keep your eyes peeled for the daily changes in Spring. Warmest wishes from Trudy